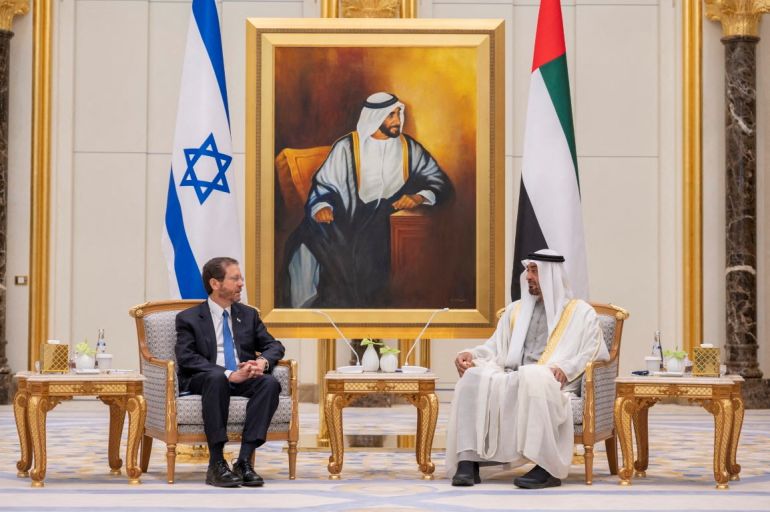

Recent Israeli escalations with Palestinians created apparent tension with the UAE but the relationship’s core remains intact, say analysts.

A series of recent statements by Israel’s far-right government has left an apparent dent in relations with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), as Tel Aviv faces tensions with regional allies.

Analysts say the heart of the relationship between the two countries – which culminated in the 2020 Abraham Accords – remains strong, but the actions of Israel’s new government make it harder for the UAE to maintain interests with Tel Aviv as well as an acceptable regional and domestic image.

Earlier this month, Israel’s Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich made inflammatory remarks denying the existence of Palestinians while standing behind a map of Israel that included Jordan within its borders.

That came amid a surge in confrontations in the occupied West Bank, with near-daily Israeli military raids, escalating violence by Jewish settlers, and a spate of individual attacks by Palestinians. Israeli forces have killed more than 250 Palestinians in the West Bank, and more than 40 Israelis have died in Palestinian attacks over the past year.

In spite of the unease around the Israeli government that took office late last year, past agreements between the two countries have pushed ahead, like the free trade agreement that was signed into effect on Sunday. The pact, which was agreed last May, removes tariffs on nearly all goods the two trade.

“Emirati officials have tried to maintain a balancing act that has become rather more difficult given the statements and actions of the new Israeli government, especially in drawing a distinction between economic and technocratic cooperation on the one hand, and political issues on the other,” said Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, fellow for the Middle East at Rice University’s Baker Institute.

Far-right sparks pressure

Smotrich’s statements claiming Palestinians were “an invention” of the past century triggered regional tensions – the map behind him depicted Israel’s borders expanded to include Jordan, Gaza, and the occupied West Bank.

Jordan responded by summoning Israel’s ambassador and its parliament voted to recommend his expulsion, while the UAE – like other Arab countries – condemned Israel by saying it “rejected the incitement rhetoric and all practices that contradict moral and human values and principles”.

The UAE also sent Khaldoon al-Mubarak, senior adviser to President Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, to reportedly warn Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government against these transgressions, according to Israeli media.

The visit coincided with reports in Israeli media that an Emirati delegation, including Foreign Minister Abdallah bin Zayed Al Nahyan, was due to arrive in Tel Aviv to discuss the remarks.

Making matters worse that week, Israeli Transport Minister Miri Regev appeared to insult the UAE by saying she would never return to Dubai following a recent visit and declaring: “I don’t like that place.”

Regev later walked back her words, posting a video on social media where she appeared to be on the phone, telling the UAE Ambassador to Israel Mohammed Al Khaja, that she was waiting for him in Israel and would be keen to visit Dubai.

Israeli Foreign Minister Eli Cohen also attempted some damage control by posting a video on Twitter to say that Dubai was “an amazing place to visit” and that “over a million Israelis have visited Dubai”.

Warnings and escalation

Yair Wallach, a lecturer in Israel Studies at SOAS, the University of London, said the UAE’s relations with what he described as an “unpredictable Israeli government” that has “very extreme elements” exposes the UAE to considerable risks.

“It is no surprise that they [the Emiratis] decided to cool down things. If we are entering a long period of instability, we’ll probably see a much less public relationship,” he explained.

Ulrichsen told Al Jazeera that al-Mubarak’s visit should be seen within the context of a visit by the foreign minister, bin Zayed, to Israel last year, during which he reportedly cautioned Netanyahu against forming a government including far-right lawmakers Itamar Ben Gvir and Smotrich if he was tasked with forming a coalition.

Observers said at the time that if Netanyahu included such lawmakers in his coalition government, he would risk upending ties with the UAE and the Abraham Accords.

But within months, Israel’s parliament swore Netanyahu in as prime minister in December 2022, inaugurating the country’s most far-right, religiously conservative government in history. Weeks of jostling had resulted in a coalition that explicitly said that its top priority is the expansion of internationally illegal settlements in the West Bank.

Shortly after Ben Gvir became Israel’s national security minister, he entered the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound in a move that Palestinians regarded as a deliberate provocation and a potential precursor to Israel taking complete control over the site.

“The trajectory of the Netanyahu government suggests that, at some point, the UAE is going to have to make a decision about whether and how it continues to engage with Israel and the Abraham Accords,” said Ulrichsen.

Core ties preserved

But according to Andreas Krieg, an associate professor at the School of Security Studies at King’s College London, the downgrading of diplomatic engagement between Israel and the UAE is merely a message for the sake of saving face domestically and regionally, while the core of bilateral ties remains intact.

“It is a PR effort more than anything … to signal to the Arab world, and most importantly its domestic audience … that it’s displeased with Israel’s treatment of Palestinians,” said Krieg, adding that global rejection of the current Israeli government was growing.

Tens of thousands of Israelis have protested across the country against the far-right government for 12 consecutive weeks. Last week, hundreds protested against Netanyahu’s plans to overhaul the Israeli judiciary as he arrived in London.

“The Abraham Accords were never about Palestine. So, whatever happens between Israel and the UAE is not necessarily linked to what’s happening between Israel and the Palestinians,” Krieg added.

Independent Israeli analyst Mayer Cohen agreed, highlighting that while recent developments were testing the Abraham Accords, the essence of UAE-Israel ties was always isolated from the Palestinian conflict.

“What’s been tainted is the UAE’s relationship with the current right-wing government. But wider Israel-UAE relations remain intact,” he told Al Jazeera.

Investments, not diplomacy

Krieg told Al Jazeera that the UAE’s relationship with Israel was governed by pragmatism, making the Gulf state “happy to continue” investing in and attracting Israeli companies, specifically in the cyber and AI technology sectors, security monitoring and other defence-related industries – as long as its economic statecraft was not affected.

“The relationship between Israel and the UAE has been built on many pillars; politics and diplomacy are important, but beyond that, there is a very strong security relationship and investments which are more important,” he added.

Emirati wealth funds intend to expand into Israel with more than $10bn in investments over the next decade, according to a Bloomberg report in 2022. Already, a major Emirati sovereign-wealth fund invested roughly $100m in venture capital firms in Israel’s technology sector last year, as business and investment ties deepened between the countries following the Abraham Accords.

Because of the many UAE investments in Israel, al-Mubarak’s visit was not about anti-Palestinian remarks, but “to check on domestic stability in Israel and to ensure Emirati investments and interests were secure”, according to Cohen.

Source: Aljazeera